Intent-First Architecture

Intent-First Architecture and Software Craftsmanship

I learned to program on punch cards. That teaches you things early—mostly about sequencing, constraints, and the cost of mistakes. When feedback takes hours or days, you don’t confuse speed with recklessness. You learn to think before you commit, because undo is expensive. Combining that intentionality, with the agility of LLM assisted code generation has been exciting.

Over the last few years, “vibe coding” has become shorthand for building software quickly with LLMs. Sometimes it produces impressive results. Sometimes it produces a mess—just faster. Most critiques focus on quality versus speed. That’s the wrong axis. The real problem isn’t vibe coding. It’s unexamined decisions without craftsmanship.

Recently, I built two open-source tools using a pattern I’ve converged on over time. One took three days to reach a usable, shippable state. The other took three weeks, and is meaningfully more complex. Both were built quickly. Neither was built casually. The difference wasn’t talent or tooling. It was discipline—and a process that puts intent ahead of implementation. I call this Intent-First Architecture.

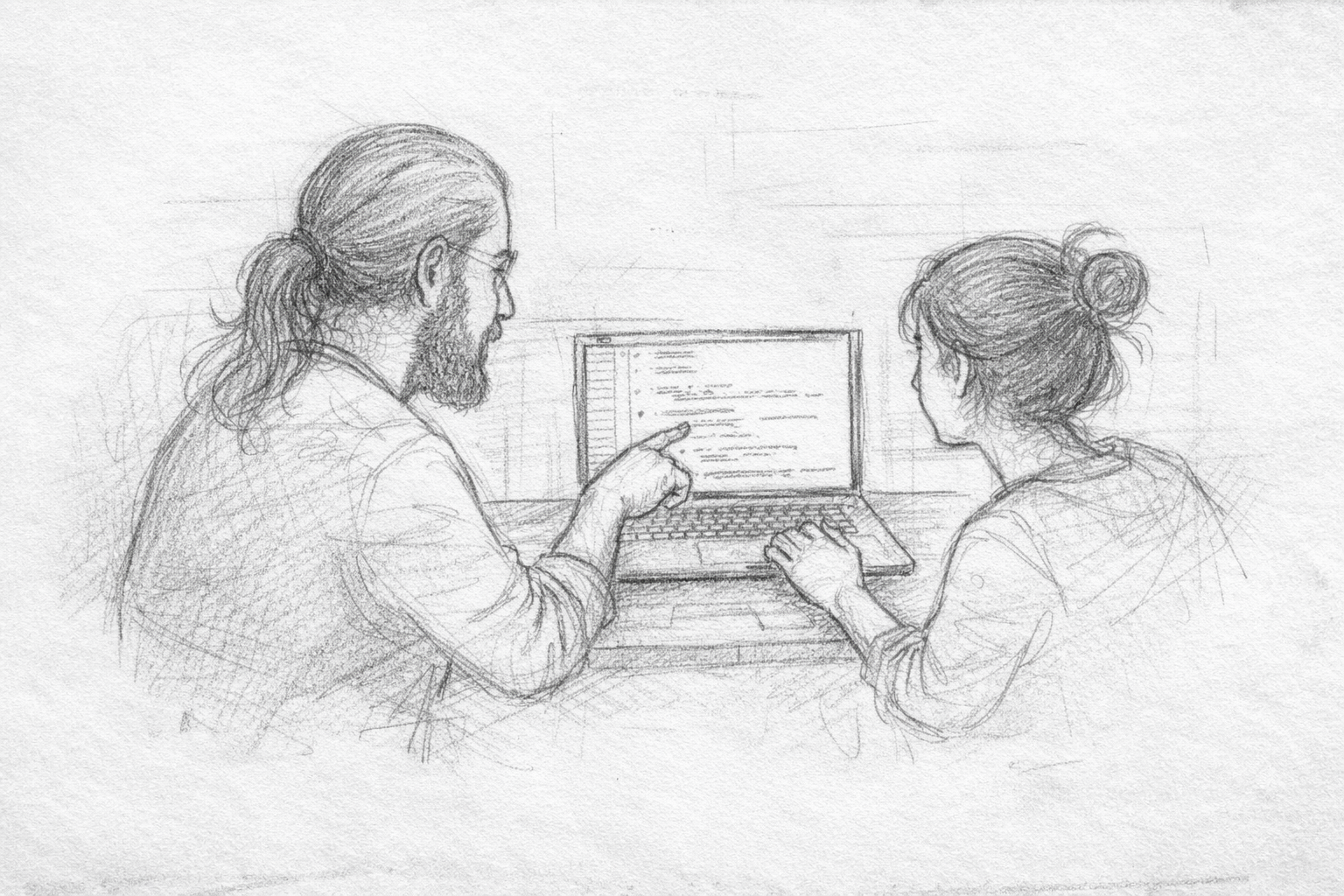

I didn’t use an LLM as an autocomplete engine. I treated it like a software engineer implementing my architecture. That changed my role. My job wasn’t typing or prompting. It was review, direction, and standards enforcement—the same role a senior engineer or architect plays on a healthy team. The LLM wrote code. I decided whether the code deserved to exist.

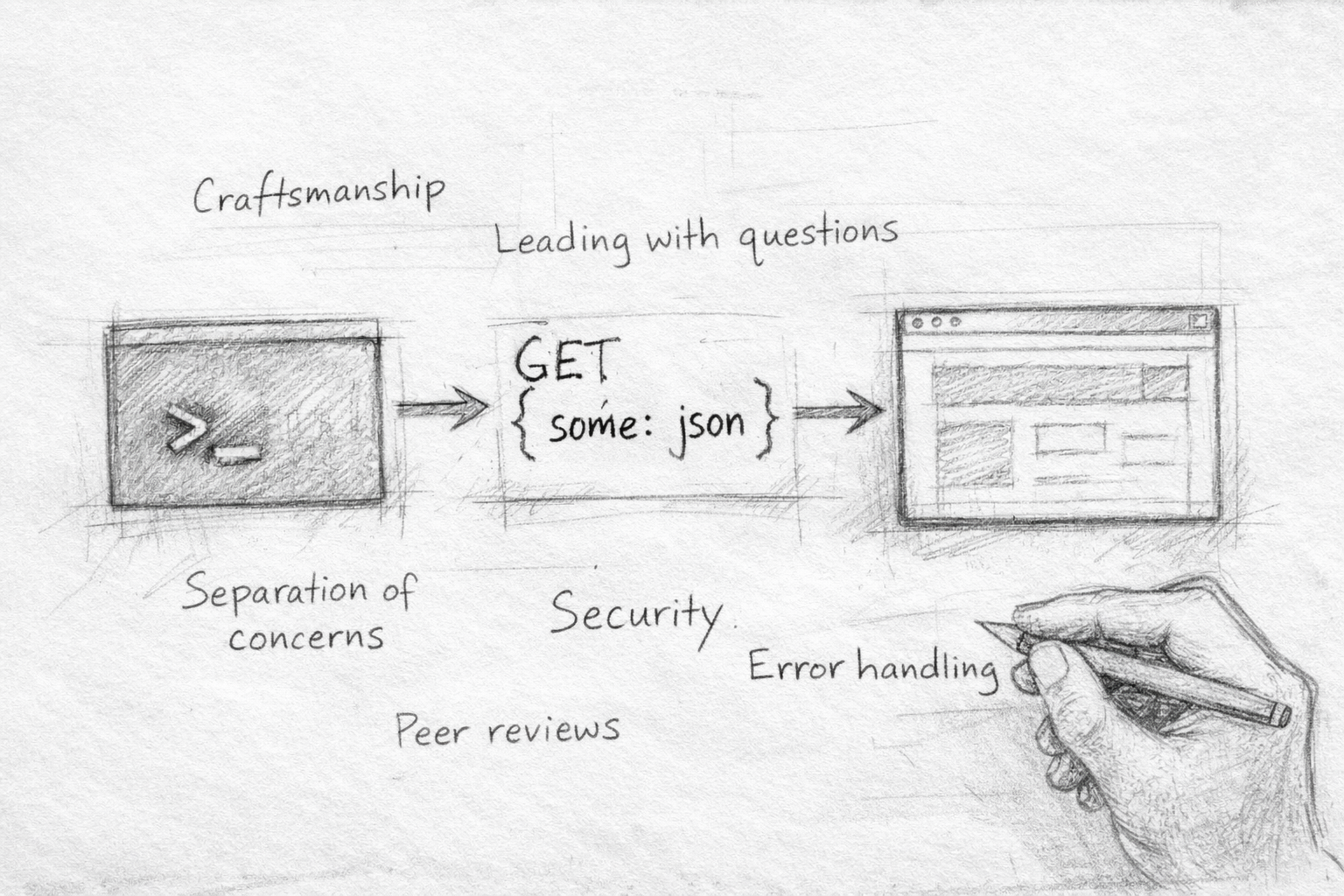

I started with a CLI. Not because I dislike UIs, but because CLIs are honest. They force you to name the problem space, define the verbs that matter, and confront workflows end-to-end. There’s no layout to hide behind. If the command structure feels awkward, the domain model usually does too. This is where exploration happens—and where it stays.

Once the CLI stabilized, I promoted it to an API. Not a CRUD service—an engine. The API exists to encode intent, enforce structure, and make automation possible. It’s where rules live, not screens. At this stage, there was still no UI, and that was deliberate. Structure comes before surface area.

Only after that did I add a UI. By then, the UI wasn’t guessing or shaping behavior. It was reflecting decisions that had already survived testing, refactoring, and real usage. The UI became obvious because the system already knew what it was and the API was refined to help the UI implement the functionality rather than some assumed implementation.

In both tools, the API uses configuration that lives in source control. That’s not an implementation detail. That is the product. Configuration is versioned, reviewed, diffed, reverted, and promoted. Once configuration reaches a releasable state, it’s packaged into a container image that extends a system-level API image. At runtime, nothing mutates. Promotion happens by building and deploying. That single constraint eliminates entire classes of failure.

Day One - Job One - Craftsmanship

From the beginning, I required unit tests where complexity lived, integration tests at service boundaries, and black-box end-to-end tests against the packaged runtime. Not later. Not after it “worked.” From the start. This wasn’t about coverage percentages. It was about confidence gradients—knowing which parts of the system could break and how loudly they would fail.

This is where most vibe-coding efforts collapse. Not because the code is bad, but because nobody is reviewing like a craftsman. I didn’t review for “does it work.” I reviewed for things experienced engineers notice instinctively: why complexity is concentrated in one file, whether a module owns a single responsibility, whether an abstraction earns its existence, whether end-to-end tests run against the exact artifact being shipped, and whether failure modes explain themselves.

The LLM never complained. It didn’t push back on refactors, resist test coverage, or argue about over-engineering. It simply responded to the quality of the questions. Over time, I got better at leading with questions instead of instructions, and the output improved accordingly. That feedback loop sharpened my craftsmanship as much as the code.

I didn’t take a class on developer experience. I enforced it. A good developer experience isn’t about shiny tooling. It’s about whether the system invites correct behavior and resists accidental misuse. Are responsibilities isolated? Is complexity visible or merely hidden? Can the system be tested in the form it actually runs? Craftsmanship answers those questions continuously, not at the end.

Each tool lives across four core repositories, an umbrella repository for intent and documentation, an API repository, an SPA repository, and a template repository for creating custom implementations. This isn’t fragmentation. It’s containment. Different concerns evolve at different rates, and craftsmanship respects that reality instead of hiding it behind a monorepo that feels simpler until it isn’t.

I don’t move fast because I ignore architecture. I move fast because I sequence commitments: exploration before hardening, structure before surface, tests before trust, packaging before mutation. Intent-first development makes vibe coding safe because intent is reviewed before behavior is locked in. Rollback is cheap. Review is deep. Standards are non-negotiable.

This is what happens when an architect practices software craftsmanship and learns how to vibe code. Not chaos. Not cowboy coding. Just momentum—with standards.

Both tools are open source— stage0_runbooks and mongodb_configurator. They’re examples, not prescriptions. The real takeaways are the pattern, and the LLM role shift. A good pattern gives the LLM clear boundries to work within, and when you let the LLM do the typing, insist on craftsmanship, and lead with questions, speed stops being reckless and starts being earned.